Advanced pharmaceutical bulletin. 13(4):799-805.

doi: 10.34172/apb.2023.074

Original Article

CRISPR/Cas9 Ablated BCL11A Unveils the Genes with Possible Role of Globin Switching

Fatemeh Movahedi Motlagh Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Hamid Reza Soleimanpour‐Lichaei Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 2

Mehdi Shamsara Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, 3

Azadeh Etemadzadeh Project administration, 1

Mohammad Hossein Modarressi Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Author information:

1Department of Medical Genetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2Department of Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Tehran, IR Iran.

3Animal Biotechnology Group, Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Tehran, Iran.

Abstract

Purpose:

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) upregulation is a mitigating factor in β-hemoglobinopathies therapy like β-thalassemia and sickle cell diseases. Finding molecular mechanisms and the key regulators responsible for globin switching could be helpful to develop effective ways to HbF upregulation. In our prior in silico report, we identified a few factors that are likely to be responsible for globin switching. The goal of this study is to experimentally validate the factors.

Methods:

We established K562 cell line with BCL11A knock down leading to increase in HBG1/2 using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Then, using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), we determined the expression level of the factors which were previously identified in our prior in silico study.

Results:

our analysis showed that BCL11A was substantially knocked down, resulting in the upregulation of HBG1/2 in the BCL11A-ablated K562 cells using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Additionally, the experimental data acquired in this study validated our prior bioinformatics findings about three potentially responsible genes for globin switching, namely HIST1H2Bl, TRIM58, and Al133243.2.

Conclusion:

BCL11A is a promising candidate for the treatment of β-hemoglobinopathies, with high HbF reactivation. In addition, HIST1H2BL, TRIM58 and Al133243.2 are likely to be involved in the mechanism of hemoglobin switching. To further validate the selected genes, more experimental in vivo and in vitro studies are required.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, Beta hemoglobinopathies, Fetal hemoglobin, Globin switching, BCL11A knockdown

Copyright and License Information

©2023 The Authors.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the original authors and source are cited. No permission is required from the authors or the publishers.

Introduction

One of the most common inherited hemoglobin disorders is thalassemia.1 Beta thalassemia patients depend on long term treatment, however they are still associated with morbidity and mortality.2 Bone marrow (BM) transplantation is by far the most definitive treatment for these patients. However, there are many problems associated with transplantation, including limited appropriate donors with identical HLA. Donors may encounter complications such as transplant rejection, and immunoglobulin reaction of host cells (graft-versus-host disease, GVHD).3 Therefore, gene therapy utilizing patients’ own hematopoietic stem cells is a preferable approach.4 Autologous gene edited hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is a definitive cure that can overcome the problems of finding BM compatible donors and GVHD.5 One of the therapeutic approaches for the edition of HSCs is to increase fetal hemoglobin (HbF) expression which can lead to the amelioration of hemoglobinopathies symptoms.6

In β-thalassemia, HbF reactivation could compensate for the β-globin deficiency and prevent the accumulation of extra unmatched α-globin chains. Various gene editing strategies have been applied to induce HbF expression as a treatment for hemoglobinopathies. BCL11A was recognized as the master repressor of HbF production by genome-wide association studies, and several studies have validated its down-regulation effect on increased HbF levels.7,8 However, genetic editing of BCL11A coding site could not be an appropriate treatment method, because its coding site has a crucial role in the hematopoietic stem cell function and the formation of lymphoid lineage. Fortunately, recent research found that disrupting the GATAA motif in the BCL11A erythroid enhancer resulted in a significant increase in HbF expression.9 Fortunately, recent studies revealed that the disruption of the GATAA motif in BCL11A erythroid enhancer led to a substantial increase in HbF expression.10

Since re-activation of HbF expression in adult erythroid cells might be a promising tool for the hemoglobin disorders therapy, it is clinically significant to discover the transcriptional regulation of globin switching. The purpose of this research is to survey the genes identified through our earlier in silico studies and introduced in our most recent publication.

For this aim, we initially established a K562 cell line with knocked-down BCL11A by “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) RNA-guided nucleases” (CRISPR/Cas9 system). Then we evaluated the expression of putative key genes found by in silico studies, including HIST1H2BL, AL133243.2, TRIM58, FAM210B, RPS27A, and BPGM.

Materials and Methods

sgRNA designing and cloning

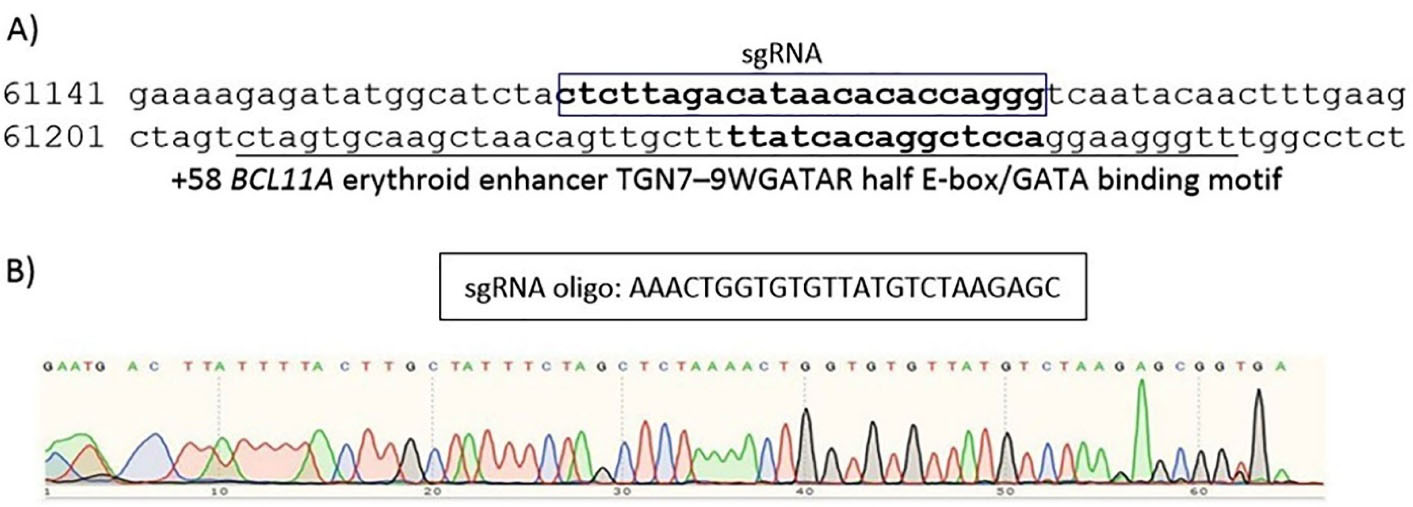

Using CRISPOR, we designed a gRNA. Considering the efficiency and off-target scores, a gRNA was selected to target erythroid enhancer of BCL11A. The position of the sgRNA used in this study are shown in Figure 1. The oligonucleotides of sgRNA, top and bottom strand, were made double stranded and then ligated into a PX458 plasmid (pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP, Addgene, Cat no: 48138) co-expressing Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 protein (SpCas9) and green fluorescent protein. The confirmation for the presence of the inserts was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the sequencing of the PCR products by Sanger’s method. The vectors were amplified in DH5α competent cells and the purification of the plasmids was performed using the QIAGEN Plasmid Plus Midi Kit.

Figure 1.

Information of our sgRNA. (A) The position of the sgRNA used in the study. (B) Confirmation of the presence of inserts using sanger sequencing

.

Information of our sgRNA. (A) The position of the sgRNA used in the study. (B) Confirmation of the presence of inserts using sanger sequencing

Cell culture

The cell line K562 was supplied from the Iranian Biological Resource Center, Tehran, Iran, and then cultured under RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 10% FBS, and at 37 °C/5% CO2.

DNA transfection by electroporation and flowcytometry

Using Bio-Rad, we electroporated 5 × 106 K562 cells with 12 µg of recombinant pX458. Electroporation settings for this cell line were 2649, 1050 μF, and 1 pulse. DNA delivery into cells was examined using Flow cytometry 48 hours after transfection. Flow cytometry analysis (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences) was conducted based upon the instructions from the manufacturer and analysis of all data were performed by Cell Quest or FlowJo (BD Biosciences).

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

The extraction of total RNA was performed by RNX-Plus kit (SINAGENE, Iran) based upon the protocol from the manufacturer. 2–5 µg RNA was reverse transcribed using the BIONEER (k-2101) Reverse Transcription kit. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed in triplicate using primers listed in Table 1 using RealQ Plus 2x Master Mix Green (Amplicon) and analyzed by a LightCycler® 96 System (Roche Molecular Systems). The target genes’ threshold cycles (Ct) were obtained from LightCycler® 96 System Software and were normalized by B2M.

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR

|

Gene

|

Sequence of primer (5’- 3’)

|

PCR Product length (bp)

|

| BCL11A(FP) |

AACCCCAGCACTTAAGCAAA |

114 |

| BCL11A(RP) |

GGAGGTCATGATCCCCTTCT |

| HBG(FP) |

TGGATGATCTCAAGGGCAC |

209 |

| HBG(RP) |

TCAGTGGTATCTGGAGGACA |

| HIST1H2BL-FP |

AAGGCCGTCACCAAGTACAC |

124 |

| HIST1H2BL-RP |

CCCCAGTGATAGGAAGAGCG |

| AL133243.2-FP |

ACACAGTTGTGCATACAGCTA |

191 |

| AL133243.2-RP |

TCCACTGTAATTCCTTTGGCTCA |

| TRIM58-FP |

AGAGGAGTCCTGAGCAGAAGTA |

143 |

| TRIM58-RP |

GTGGCGGGATCCAGCTTTAC |

| FAM210B-FP |

AGCGTCAGCTGCACAGAG |

158 |

| FAM210B-RP |

GGCATGTCCACACCACTTGA |

| RPS27A-FP |

CAAGATCCAGGATAAGGAAGGAAT |

147 |

| RPS27A-RP |

GCACCACCACGAAGTCTCAA |

| BPGM-FP |

AAAACACCTGGAAGGTATCTCA |

96 |

| BPGM-RP |

GCACGCAGGTTTTCATCCAA |

Statistical analysis

The analysis of relative gene expression was done by the formula 2−ΔΔCT method using Ct value. The error bars represent the standard deviations. Data were analyzed using two group t test. P < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance (**P value < 0.01 ***P value < 0.001 ****P value < 0.0001). GraphPad Prism 5 was used for calculations (GraphPad Software, San Diego).

Results and Discussion

Detecting key genes involved in the globin switching and knowing their interactions helped us find more evidence for its molecular mechanisms.

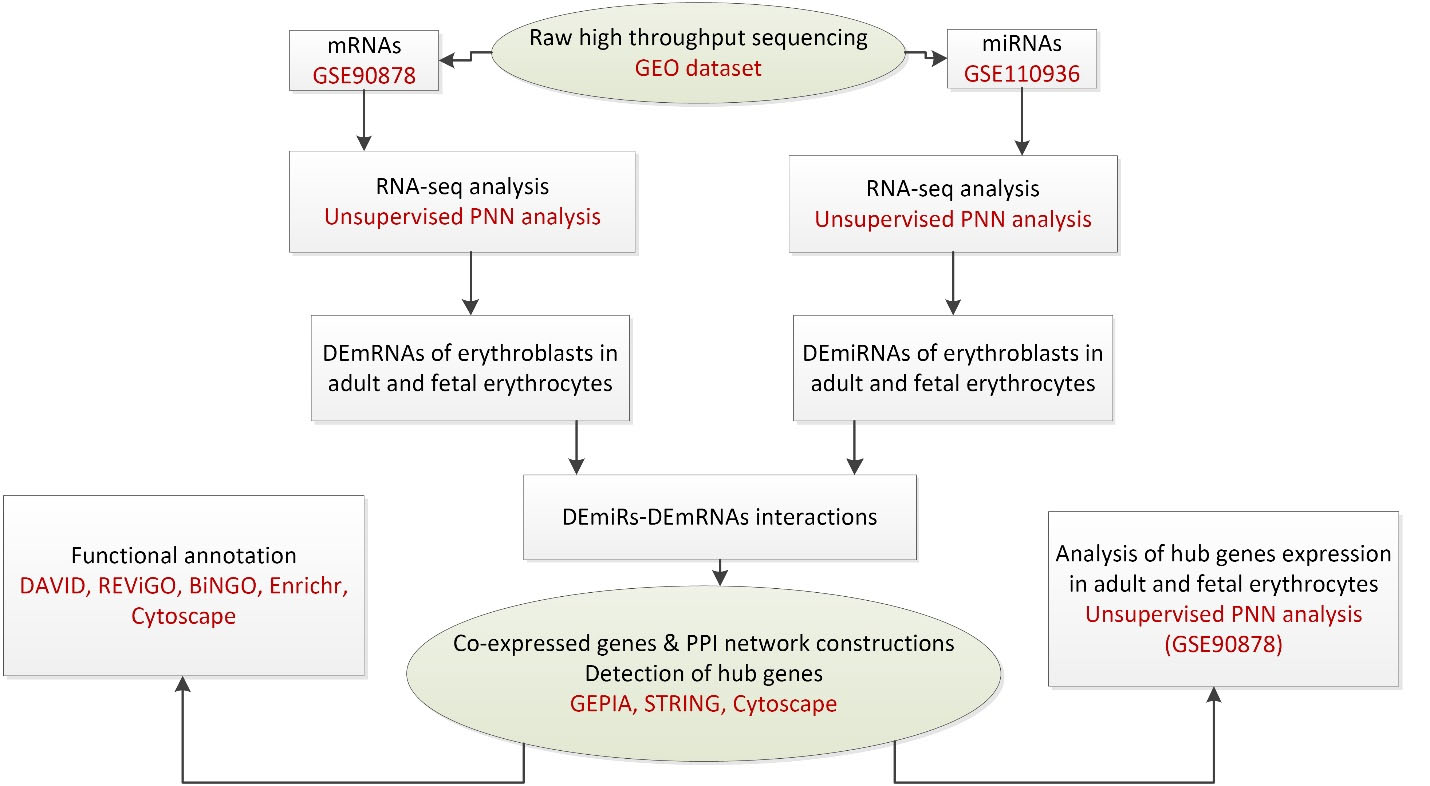

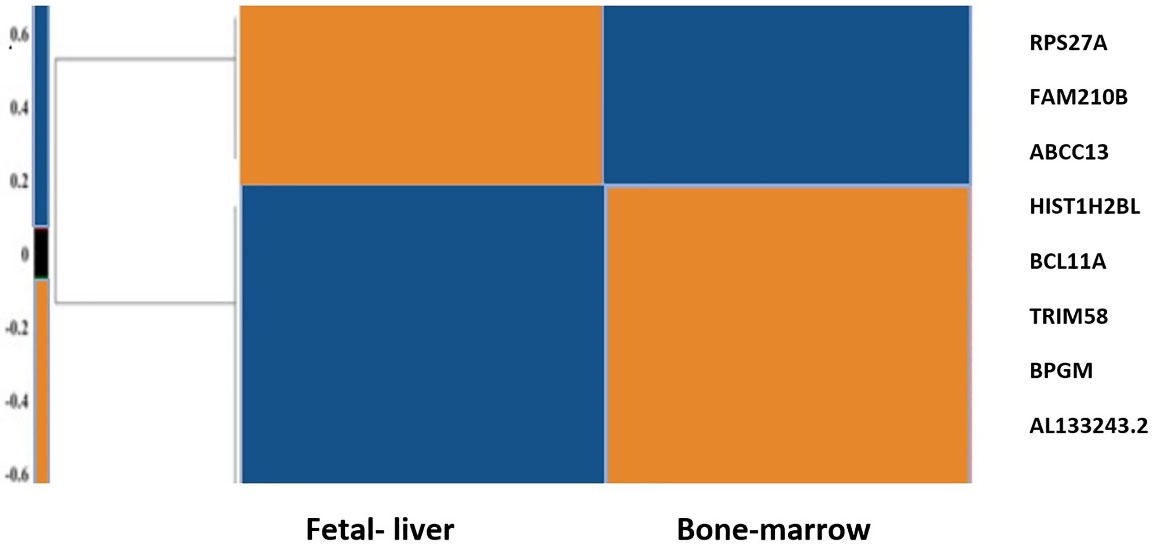

In our prior study, we used bioinformatics and systems biology methods to introduce probable hub genes that play roles in the globin switching process. For this aim, RNA-seq data analysis was used to define DEmRNAs (differentially expressed mRNAs) and DEmiRs (differentially expressed miRNAs) in adult and fetal erythroblasts. Moreover, we used multiple databases to construct co-expression and protein protein interaction (PPI) networks to find key mRNAs, as depicted in the flow diagram of our study in Figure 2. The hub genes included Histh2bl, Al13243.2, Trim58, Bpgm, and Fam210b in the coexpression network, as well as RPS27A in the PPI network. In addition, we surveyed the expression changes of the hub genes in adult and fetal erythrocytes using RNA-seq analysis of the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) samples. As indicated in Figure 3, the expression of the bcl11a, rps27a, and fam210b were decreased, while that of the hist1h2bl, al1332433.2, and trim58 were increased in adult erythrocytes. It is obvious that experimental studies are required to consider these genes as key factors in globin switching. In this study, we designed the experiment to confirm the results of our previous in silico study. Therefore, we established a K562 cell line with a decrease in BCL11A by CRISPR/Cas9 system. Then, we evaluated the expression of the hub genes found by in silico study including HIST1H2BL, AL133243.2, TRIM58, FAM210B, RPS27A, and BPGM.11

Figure 2.

The flow diagram of bioinformatics study.11

.

The flow diagram of bioinformatics study.11

Figure 3.

Heat map of the hub genes. mRNA expression was normalized in the range of -3 to 3. The down-regulated and up-regulated genes are colored blue and orange, respectively.11

.

Heat map of the hub genes. mRNA expression was normalized in the range of -3 to 3. The down-regulated and up-regulated genes are colored blue and orange, respectively.11

Cloning of gRNAs into PX458

After annealing sgRNA oligos, they were ligated into PX458 plasmids. Ligated plasmids were transformed into chemically competent bacterial cells and plated on agar plates containing the ampicillin. Clones were picked after 24 hours, inoculated into 5 mL LB broth medium supplemented with ampicillin, and finally cultured overnight. The plasmids were then extracted and the confirmation of the inserts was performed by PCR and subsequent sequencing (Figure 3).

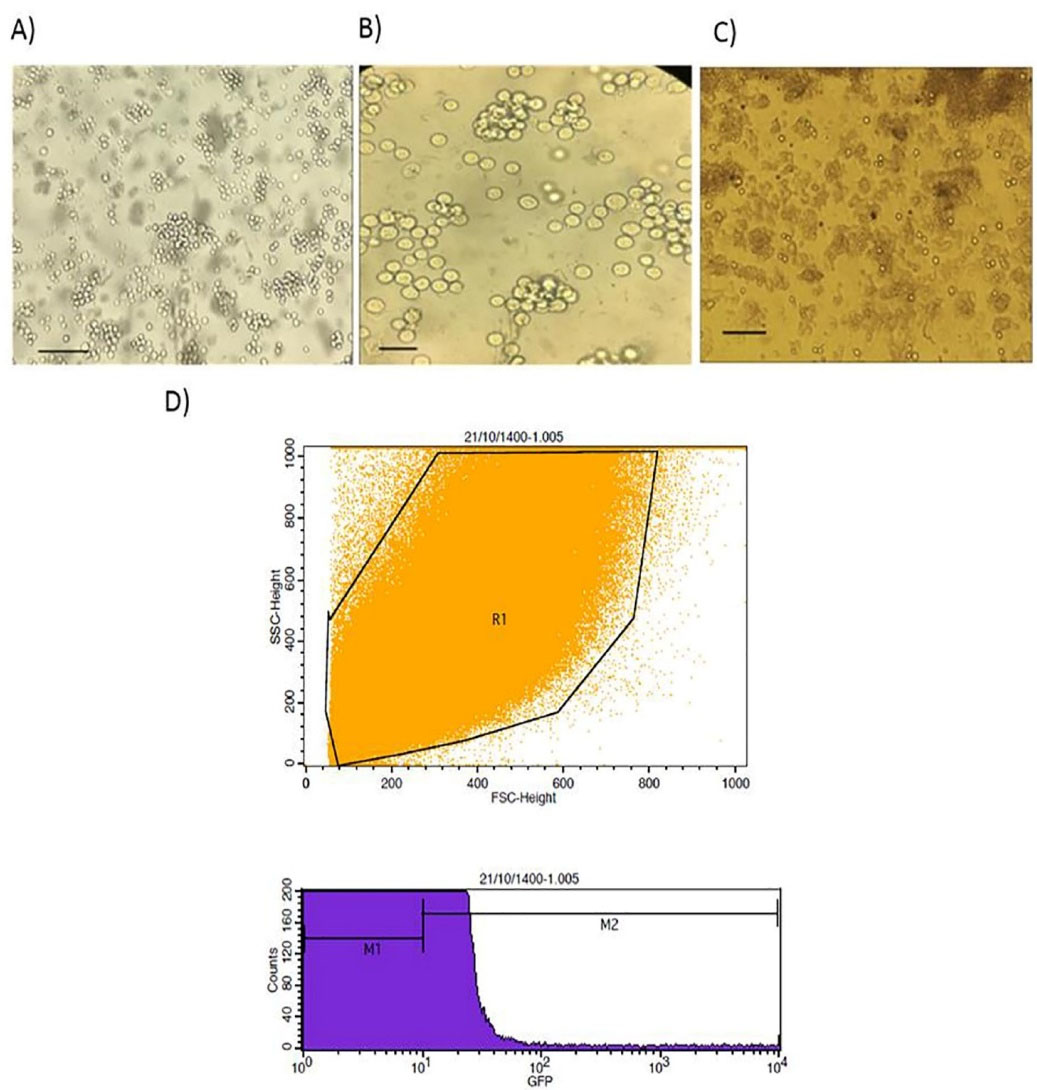

Transfection of K562 cell line by electroporation

K562 cell line was transfected with PX458 plasmid harboring gRNA using electroporation. Transfection efficiency was determined by flowcytometry analysis after 48 hours. The results of flowcytometry analysis showed that about 12% of the electroporated cells were successfully transfected (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

the results of transfection. (A) K562 cell line Bars: 100 µm, (B) K562 cell line Bars: 40 µm, (C) K562 cell line post transfection (G1 cells) Bars: 100 µm, and (D) The results of flow cytometry analysis 48 hours post transfection

.

the results of transfection. (A) K562 cell line Bars: 100 µm, (B) K562 cell line Bars: 40 µm, (C) K562 cell line post transfection (G1 cells) Bars: 100 µm, and (D) The results of flow cytometry analysis 48 hours post transfection

Disruption of the BCL11A enhancer upregulated HBG1/2 expression in K562 cell lines

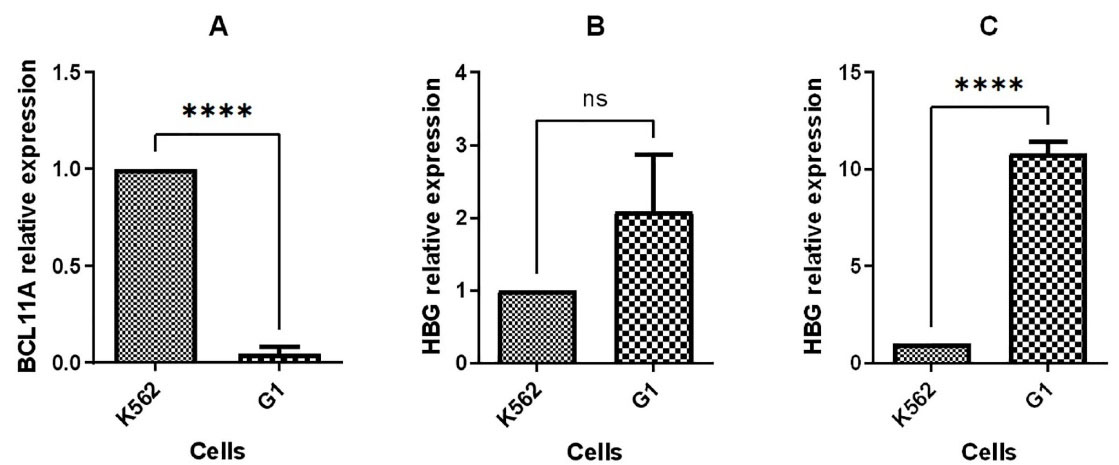

48 hours post transfection, expression changes of BCL11A, HBG1/2, and the putative hub genes, which were earlier introduced by our prior in silico study, were analyzed. The results showed that the BCL11A expression was substantially decreased (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR to compare gene expression in G1 with K562 cell line, (A) BCL11A expression 48 hours post transfection, (B) HBG1/2 expression 48 hours post transfection, and (C) HBG1/2 expression 96 hours post transfection. (**P value < 0.01 ***P value < 0.001 ****P value < 0.0001, ns: not significant)

.

Quantitative RT-PCR to compare gene expression in G1 with K562 cell line, (A) BCL11A expression 48 hours post transfection, (B) HBG1/2 expression 48 hours post transfection, and (C) HBG1/2 expression 96 hours post transfection. (**P value < 0.01 ***P value < 0.001 ****P value < 0.0001, ns: not significant)

Moreover, upregulation of HBG1/2 was observed with 2-fold and 10-fold increase in mRNA level in BCL11A knocked-down cells compared to non-transfected cells at 48 hours and 96 hours post transfection, respectively (Figure 5).

Previous studies have validated BCL11A as a key HbF silencing factor that regulates the developmental globin switching.12 BCL11A binds to the location at the HBG1/2 gene’s proximal promoters to silence γ-globin gene. Some studies provide detailed information on the mechanism by which BCL11A and its co-factors act.13,14 In a recent study, the efficiency of three methods including BCL11A and KLF1 knock down as well as HBG1/2 promoter editions was compared. The findings suggest that knocking down KLF1 may interfere with the expression of cell-cell interaction genes like ITGA2B and CD44, microcytosis genes like AQP1, and cancer genes like FLI-1. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that BCL11A knock down was safer than the other methods, with the ability to upregulate HbF more than four folds in BCL11A-edited samples compared to control sample.15

This research, in line with the previous studies, demonstrated that inactivation of BCL11A enhancer, located in the second intron, can stimulate fetal hemoglobin synthesis and could be applied as a possible gene therapy strategy for β-hemoglobinopathies.16 The erythroid-specific BCL11A enhancer has been suggested as the most demanded candidate for clinical use.17 Previous research has suggested that editing based on NHEJ approaches might be more efficient than HDR-based editing.18

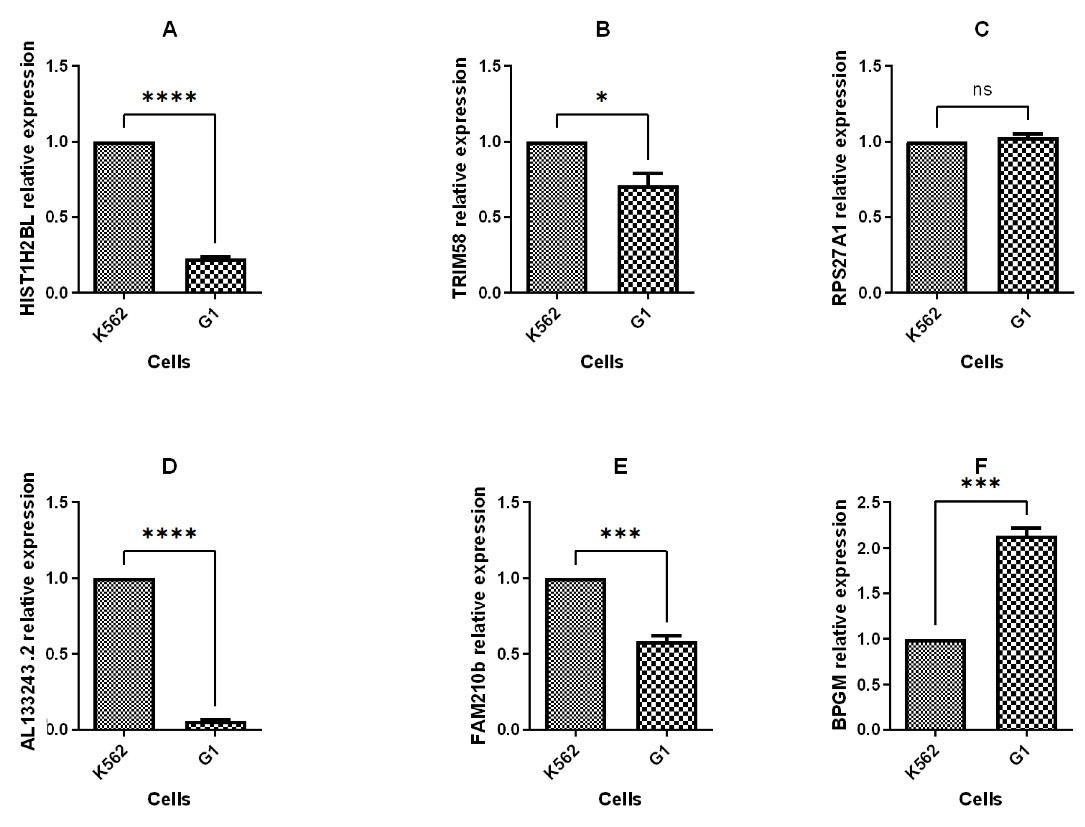

Evaluation of hub genes expression in transfected K562 cell lines

The expression of hub genes found by in silico study including HIST1H2BL, AL133243.2, TRIM58, FAM210B, RPS27A, and BPGM was evaluated using q-PCR 48 hours post transfection. The q-PCR analysis revealed that BPGM was upregulated, while HIST1H2BL, AL133243.2, TRIM58, and FAM210B were down regulated, and RPS27A expression remained unchanged after transfection (Figure 6). The q-PCR results and bioinformatics data for three genes, including HIST1H2BL, TRIM58, and AL13243.2, were consistent.

Figure 6.

Quantitative RT-PCR to compare hub genes expression in G1 with K562 cell line. (**P value < 0.01 ***P value < 0.001 ****P value < 0.0001, ns: not significant)

.

Quantitative RT-PCR to compare hub genes expression in G1 with K562 cell line. (**P value < 0.01 ***P value < 0.001 ****P value < 0.0001, ns: not significant)

TRIM58, an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, has been demonstrated to be crucial in late erythropoiesis.19 Previous research identified HIST1H2BL, which encodes a member of the H2B histone family, as a target gene for the BCL11A transcription factor. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that HIST1H2BL is a regulator of transcription using chromatin organization. This information implies that other transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, such as chromatin architecture, may potentially control the production of HbF.11,20

AL133243.2 is an lncRNA. It has been established that gene expression is regulated by lncRNAs via DNA, RNA, and protein interactions.21 LncRNAs have many important functions in erythropoiesis, like globin switching.22 In a previous study we demonstrated that AL133243.2 may act as a regulator at the transcriptional and translational levels.11

Conclusion

To obtain insights into the globin switching process, we have used bioinformatics and experimental approaches to find the probable key genes. This approach enabled us to identify some genes that may increase HbF levels.

In summary, we have demonstrated that BCL11A knock down can be used to induce HBG1/2 expression to therapeutically relevant levels. In comparison to globin gene addition, genome editing approach to obtain globin reverse switch would have the benefit of high-level production of endogenous γ-globin.18

In a prior bioinformatics study, we identified six genes with potential key roles in globin switching; however, in the current study only three genes (out of the six genes) were experimentally validated for their possible function in globin switching.11

The safety and specificity of gene editing are critical parameters for clinical use of therapeutic tools.17 Our results reveal the function of an lncRNA, AL133243.2, in the HbF production. Defining the role of lncRNA in the post-transcriptional control of HbF may prompt the investigation of therapeutic elements that would prevent widespread alterations to the transcriptome.

Overall, our findings have identified potential targets for therapeutic reactivation of fetal hemoglobin. The clinical application of the genes involved in HBG reactivation requires further in vitro and in vivo research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study approved by the ethics committiee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study (Code: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1398.762).

References

- Kutlar F. Diagnostic approach to hemoglobinopathies. Hemoglobin 2007; 31(2):243-50. doi: 10.1080/03630260701297071 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jackson LA, Hill QA, Ciantar E. The management of haemoglobinopathies in pregnancy and childbirth. ObstetGynaecol 2022; 24(2):109-18. doi: 10.1111/tog.12805 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Tong Y, Liu XZ, Wang TT, Cheng L, Wang BY. Both TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 directly target the HBB IVS2-654 (C > T) mutation in β-thalassemia-derived iPSCs. Sci Rep 2015; 5:12065. doi: 10.1038/srep12065 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ou Z, Niu X, He W, Chen Y, Song B, Xian Y. The combination of CRISPR/Cas9 and iPSC technologies in the gene therapy of human β-thalassemia in mice. Sci Rep 2016; 6:32463. doi: 10.1038/srep32463 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou C, Goussetis E. HSCT remains the only cure for patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia until gene therapy strategies are proven to be safe. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021; 56(12):2882-8. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01461-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana M, Antoniani C, Miccio A. Gene therapy for β-hemoglobinopathies. Mol Ther 2017; 25(5):1142-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Demirci S, Zeng J, Wu Y, Uchida N, Shen AH, Pellin D. BCL11A enhancer-edited hematopoietic stem cells persist in rhesus monkeys without toxicity. J Clin Invest 2020; 130(12):6677-87. doi: 10.1172/jci140189 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Canver MC, Smith EC, Sher F, Pinello L, Sanjana NE, Shalem O. BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature 2015; 527(7577):192-7. doi: 10.1038/nature15521 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Luc S, Huang J, McEldoon JL, Somuncular E, Li D, Rhodes C. Bcl11a deficiency leads to hematopoietic stem cell defects with an aging-like phenotype. Cell Rep 2016; 16(12):3181-94. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.064 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahimmanesh I, Boshtam M, Kouhpayeh S, Khanahmad H, Dabiri A, Ahangarzadeh S. Gene editing-based technologies for β-hemoglobinopathies treatment. Biology (Basel) 2022; 11(6):862. doi: 10.3390/biology11060862 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Movahedi Motlagh F, Soleimanpour-Lichaei HR, Emami A, Kadkhoda S, Shamsara M, Rasti A. Bcl11a and the correlated key genes ascribable to globin switching: an in silico study. Cardiovasc HematolDisord Drug Targets 2022; 22(2):128-42. doi: 10.2174/1871529x22666220617125731 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Peslak SA, Ren R, Khandros E, Qin K, Keller CA. HIC2 controls developmental hemoglobin switching by repressing BCL11A transcription. Nat Genet 2022; 54(9):1417-26. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01152-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Métais JY, Doerfler PA, Mayuranathan T, Bauer DE, Fowler SC, Hsieh MM. Genome editing of HBG1 and HBG2 to induce fetal hemoglobin. Blood Adv 2019; 3(21):3379-92. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000820 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qin K, Huang P, Feng R, Keller CA, Peslak SA, Khandros E. Dual function NFI factors control fetal hemoglobin silencing in adult erythroid cells. Nat Genet 2022; 54(6):874-84. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01076-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lamsfus-Calle A, Daniel-Moreno A, Antony JS, Epting T, Heumos L, Baskaran P. Comparative targeting analysis of KLF1, BCL11A, and HBG1/2 in CD34 + HSPCs by CRISPR/Cas9 for the induction of fetal hemoglobin. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1):10133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66309-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Caulier AL, Sankaran VG. Molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate human erythropoiesis. Blood 2022; 139(16):2450-9. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011044 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Demirci S, Leonard A, Tisdale JF. Genome editing strategies for fetal hemoglobin induction in beta-hemoglobinopathies. Hum Mol Genet 2020; 29(R1):R100-R6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa088 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Antoniani C, Meneghini V, Lattanzi A, Felix T, Romano O, Magrin E. Induction of fetal hemoglobin synthesis by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the human β-globin locus. Blood 2018; 131(17):1960-73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-811505 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thom CS, Traxler EA, Khandros E, Nickas JM, Zhou OY, Lazarus JE. Trim58 degrades Dynein and regulates terminal erythropoiesis. Dev Cell 2014; 30(6):688-700. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.07.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zovkic IB. Epigenetics and memory: an expanded role for chromatin dynamics. CurrOpinNeurobiol 2021; 67:58-65. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2020.08.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL, Huarte M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021; 22(2):96-118. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00315-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Shi L. Long non-coding RNAs during normal erythropoiesis. Blood Sci 2019; 1(2):137-40. doi: 10.1097/bs9.0000000000000027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]